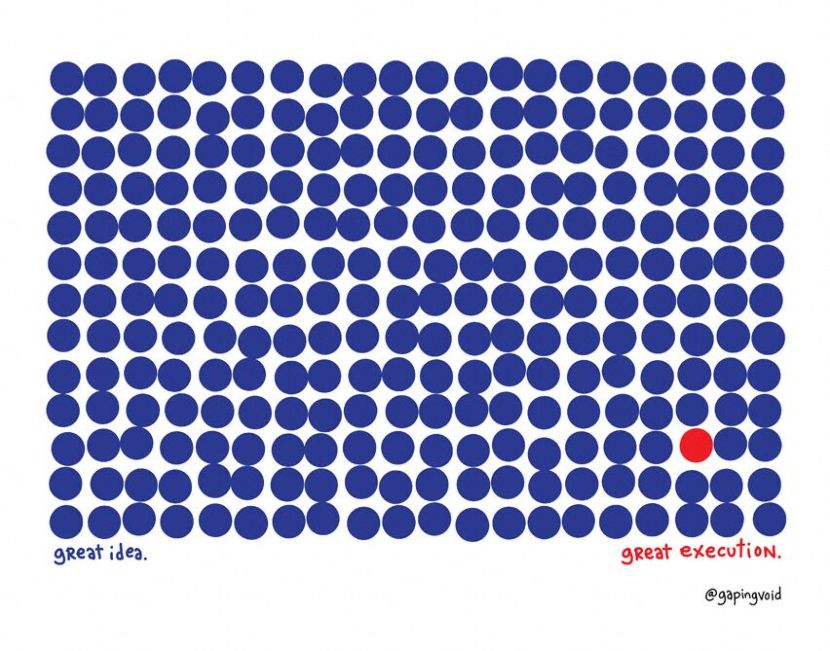

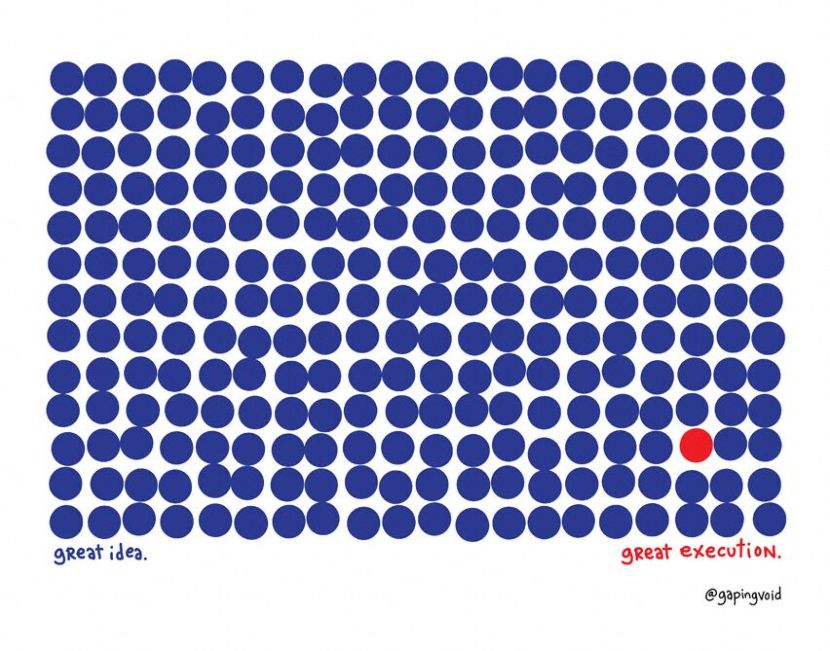

Image via @gapingvoid

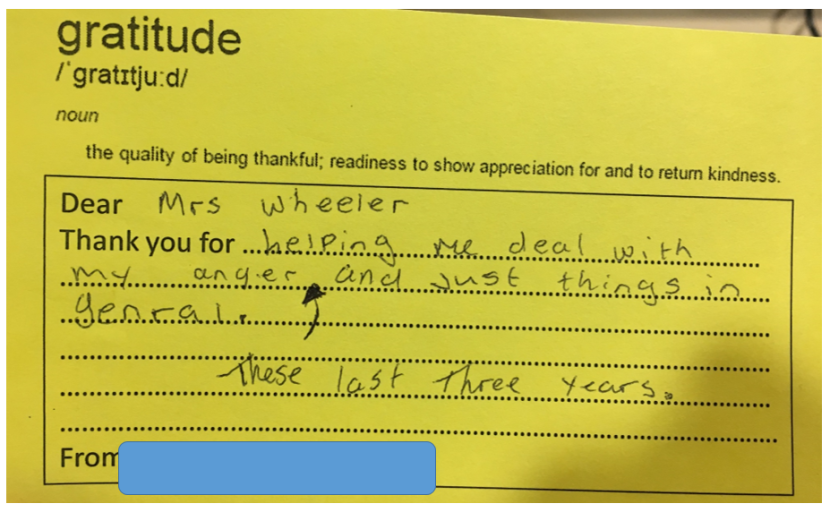

If learning happens over a period of weeks, months and years.

Is lesson planing always carried out with student learning in mind?

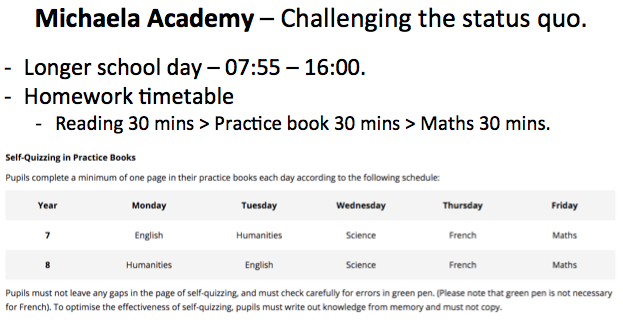

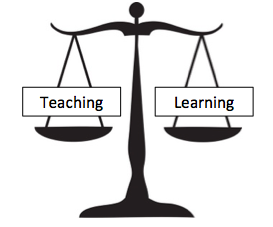

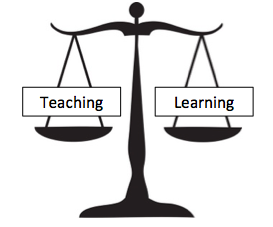

Recently I have led a series of talks/sessions/workshops on the challenges of leading teaching & learning across a school. What has struck me as somewhat odd is the number of people that hear the phrase ‘teaching & learning’ but only really register the ‘teaching’ part. Teaching without any understanding of how people learn or what learning is, conjures up thoughts of the blind leading the blind. What does your school focus on? Is their balance between teaching and learning with links between the two?

What does your school focus on?

After reading books like ‘Why students don’t like school’ and ‘the hidden lives of learners’ I can’t help but think about learning whenever I’m planning a lesson or reflecting upon my teaching. This has led me to reflect further on lesson planning and a few questions that teachers could consider, to focus the planning of a lesson to maximise learning:

1. What is the desired learning outcome?

2. What do I want students to think about at different points during the lesson?

3. Will the activity make them think hard about the desired content or distract them from it?

4. How will I link new knowledge to students existing knowledge base?

5. How will I model the learning outcome?

What I think about when I plan a lesson.

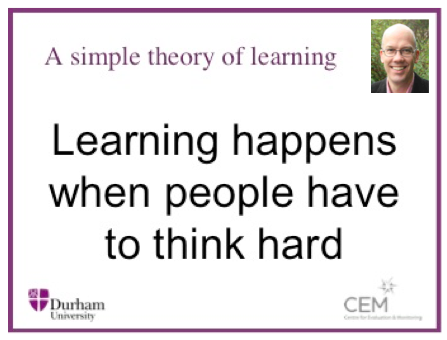

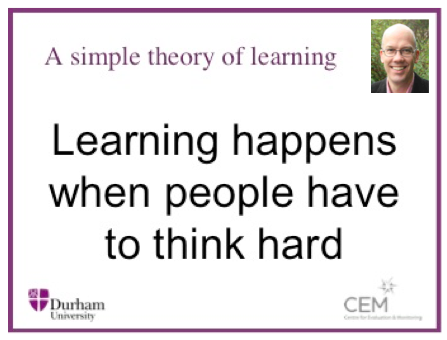

I always go back to a definition of learning by Professor Coe that has stuck with me. and stays at the forefront of my mind…

So I think about the one thing I want my students to learn and then design a sequence that will enable them to think hard about the knowledge and apply / practice the desired skills. If an activity does not contribute to the learning then it doesn’t form part of the lesson.

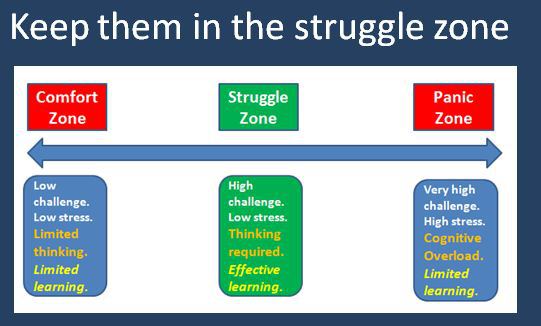

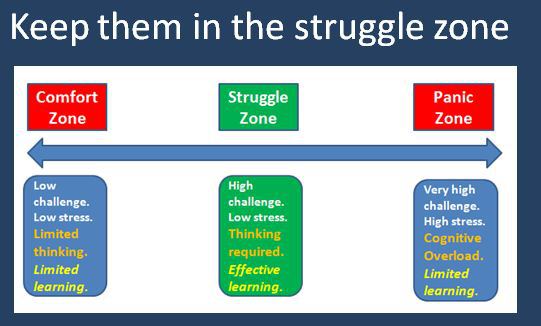

The spectrum below (created by Shaun Allison) expertly depicts what teachers should be aiming for – the struggle zone. Learning should be difficult enough that students grapple with the content but not so difficult that it flies straight over their heads or so easy that it doesn’t require any real thought at all.

Image via Shaun Allison

On a recent trip to Malaysia (so recent I’m currently sat in my wife’s parents house in Malaysia writing this post) me and my wife decided to fly direct from London to Kuala Lumpur, with a 3 month old in tow it seemed like a sensible idea. Our objective was to get to Malaysia as quickly as possible with the least amount of hassle and distraction. Now we could have flown from London to Amsterdam, wait a few hours flown to Dubai, wait several hours before flying onto Kuala Lumpur which would have used up almost a whole day on travelling. This option might have saved us a little money but would have almost certainly used up lots of time and energy. This scenario made me think about lessons and the quickest possible route to learning.

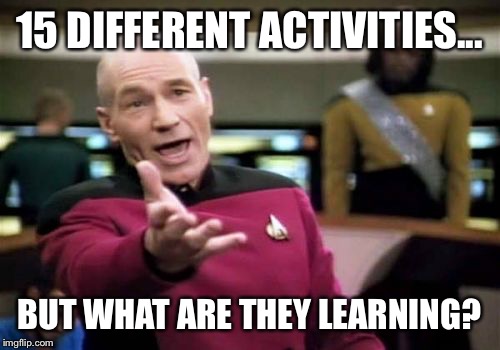

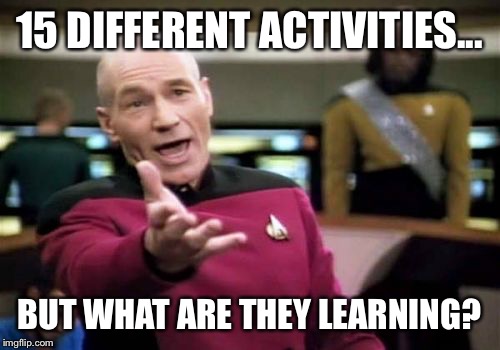

I’ve observed a number of lessons where the objective has been really clear on the learning that the teacher wants the students to engage with, but the students have been held back by a flurry of activities with questionable links to the desired learning. This leads me to think that as teachers, if there is a direct route to the learning we should take it. When planning a lesson, if the objective is for students to learn X why should they embark upon an array of activities that eventually lead them to X or miss the destination altogether? We sometimes get bogged down in planning lessons to fill time using multiple activities (that sometimes take us off course) to buffer the learning rather than getting straight to the learning.

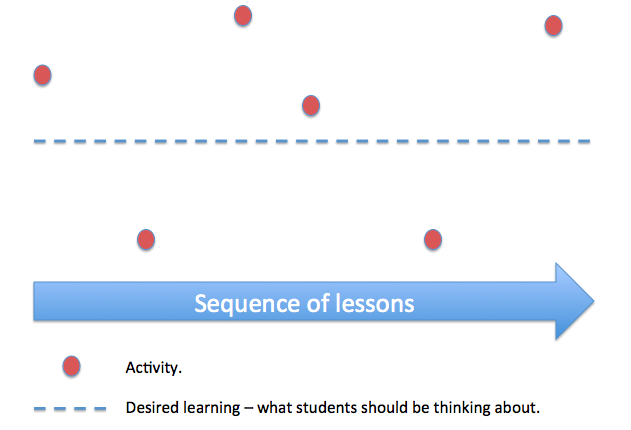

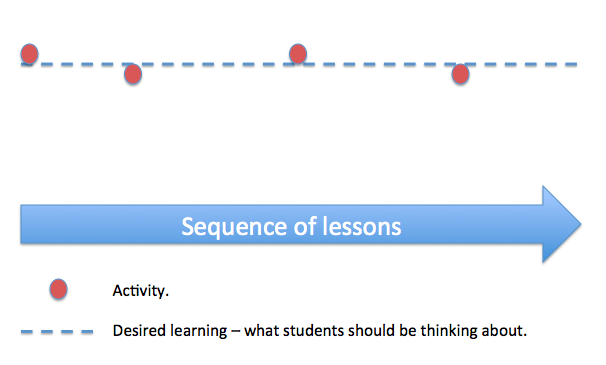

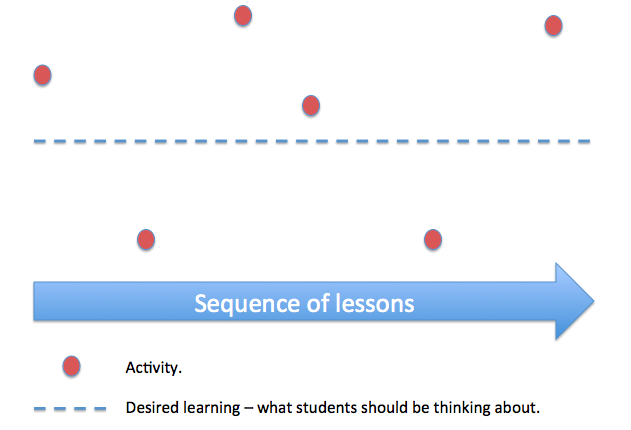

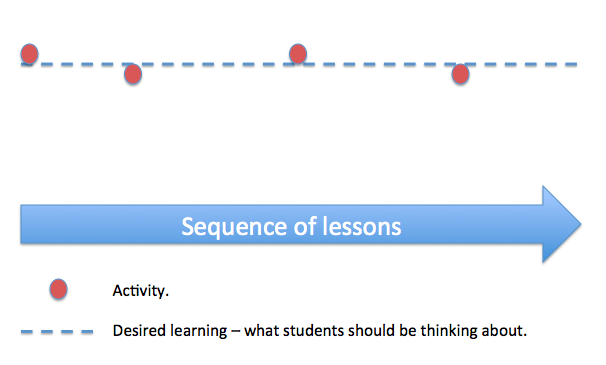

Consider the two diagrams below – which one best represents your lessons?

A sequence of lessons that provide a buffer to learning.

A sequence of lessons focused around the desired learning.

When planning a lesson it’s important to keep in mind the learning and design activities that will enable students to think hard about the desired learning by spending time in the struggle zone and allow time for students to practice the application of desired knowledge / skills.

Habits of highly effective lesson planning.

This blog post by Pepe Mccrea outlines habits of highly effective planning. Below are the 7 habits with a few key extracts from Pepe’s blog.

1. Start with the end in mind.

Excessive clarity – The clearer you are about where you want them to get, the better you’ll be able to help them get there.

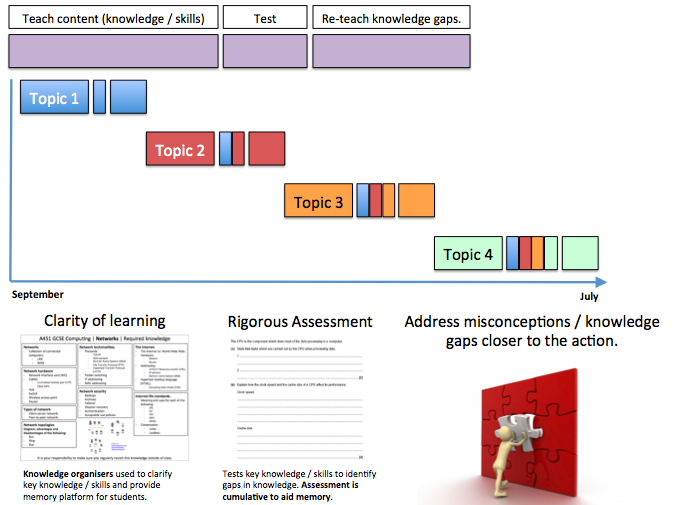

2. Take the shortest path.

Don’t waste time designing overly complex learning experiences. What is the least I need to say to explain this concept to my students? What is the least amount of information I need to give them before they can get started?

3. Assess reliably and efficiently.

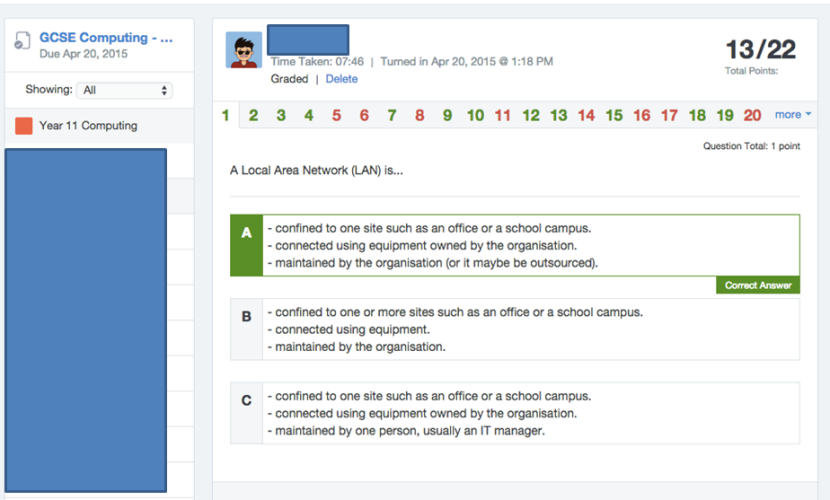

Hinge questioning Asking the whole class to: answer a multi-choice question using hand-signals; or show their thinking using mini-whiteboards.

Exit ticketing Giving students 3 questions to answer on a sheet of paper which they have to hand to you as they walk out the door.

4. Build learning that lasts.

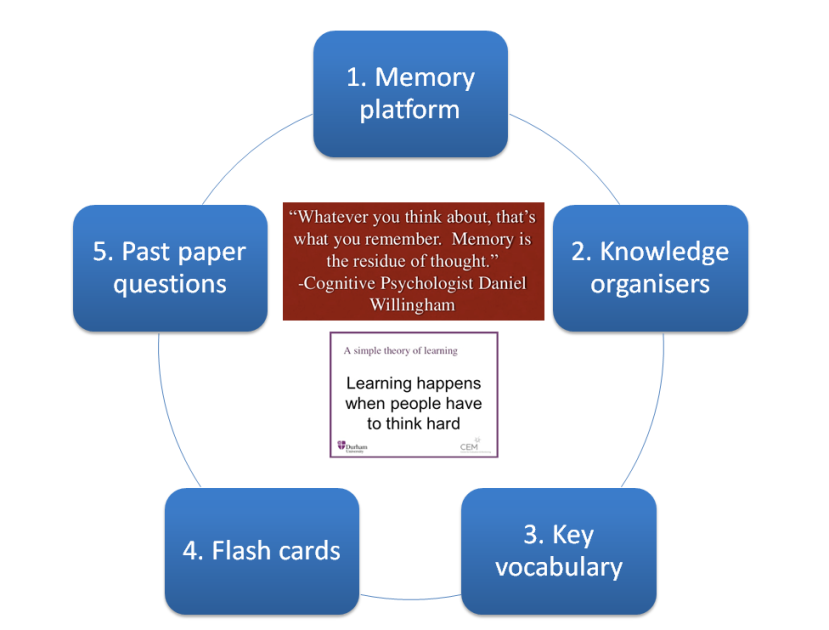

Plan for thinking As Daniel Willingham so eloquently puts it, ‘learning is the residue of thought’. Plan what you want your students to think.

Anchor thinking David Ausubel tells us that ‘what students already know is the most important factor in what they can learn’. Design activities to help your students tap into what they know and make connections with what they’re going to learn about.

5. Anticipate the unexpected.

Increase your impact further by looking for points in your lesson where students are likely to struggle, make mistakes or develop misconceptions.

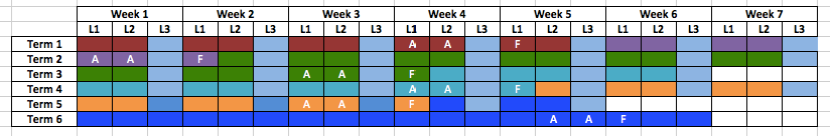

6. Move towards inter-lesson planning.

The relationship between lessons is just as important as what happens within them.

7. Plan better together.

Sharing your planning and practice not only brings fresh eyes to old problems and helps us articulate what we’re doing and why, but it also spreads our understanding of what works (and what doesn’t) amongst our profession.

Summary.

We often have lots of great ideas for lesson activities but must consider the execution of them and the effect they will have on the desired learning. When planning a lesson consider:

– working backwards from where you want students to end up.

– what you want students to think about at different points in the lesson and how your planned activities will foster that thinking.

– the quickest path to the learning – don’t waste time with lots of activities that just keep students busy – focus on tasks that enable students to grapple with knowledge / skills in the ‘struggle zone.’