Tagged: education

Stop disadvantaging the disadvantaged // Some practical tips for teaching & learning.

There are no shortcuts or golden tickets. Get teaching right first. [Sir John Dunford]

Education is not just for the elite. It is for everyone regardless of the circumstances into which they are born. In order to ensure students are every background get the same opportunities as everyone else, teachers have to pay meticulous attention to disadvantaged students for it’s those students who stand to gain the most from effective teaching and learning.

‘Get teaching right’ or ‘quality first teaching’ gets mentioned a lot when talking about ‘closing the gap’ between disadvantaged students and their peers but what does this actually mean? Saying these things repeatedly is not overly useful – it doesn’t encourage teachers to change their teaching habits or reflect on their practice. Should teachers be doing things differently for disadvantaged students in lessons day to day? Probably not, but disadvantaged students should be at the top of a teachers thought process when teaching as it’s these students who stand to gain the most from teaching that increases subject knowledge and provides lots of opportunities to bring that information to mind.

What does it mean to be disadvantaged?

Dr Nicholls has a great insight into disadvantaged students here. He talks about the need to disrupt the loop of unequal outcomes for disadvantaged students and has come up with a list (this does not assume all disadvantaged students are affected by these things) that highlights some of the key factors that may identify a young person as disadvantaged…

Another significant factor that relates to learning is that disadvantaged students tend to arrive at secondary school (and primary school) with a lower number of words in their vocabulary and a distinct lack of cultural knowledge (compared to their peers) which restricts their understanding and delays their progress. Joe Kirby makes a great argument for scientific based curriculum design here that would certainly help close the knowledge gap for disadvantaged students.

What can teachers do day to day?

Routines. A lack of routine can disrupt the start of a lesson, waste time handing out books, lead to confusion and a general misunderstanding of expectations in a classroom, all of which will affect learning for students. Consider:

- How will students enter your classroom and what will they need to do upon being seated? For example what if the expectation was that students had 30 seconds to enter and get seated and then immediately completed a short quiz of 4 or 5 questions that tested their knowledge of lesson content from last week, last month, last term and last year? The accumulative effect of this interleaved approach on learning could increase a students knowledge over time whilst providing a smooth start to the lesson that focuses on learning from the outset.

- Also consider your routines/expectations for:

- getting students to be silent.

- TRY: ‘3,2,1, eye contact’ and explain to students that once you get to 1 all students should have eye contact with you. This is a great way of getting students attention. Be persistent, habits don’t form over night.

- questioning and how students should respond [see below].

- handing out books / resources – what’s the most time efficient way to do this? Are students trained in this so that it becomes automatic? Every second counts!

- circulating the room whilst students are working? Do you check in on disadvantaged students first?

- working environment during a task – what is the default noise level? Purposeful, directed talk amongst students is useful for developing understanding but when this is not part of the task do students need to talk? A noisy classroom makes it difficult to concentrate for long periods of time.

- getting students to be silent.

Directed questioning. No reasonable person would expect a teacher to know every disadvantaged student that they teach (especially with large cohorts) so use your annotated seating plan.

- TRY:

- Don’t be afraid to have your seating plan in your hand whilst questioning and use it to ensure disadvantaged students get questioned regularly. I’ve seen teachers use this strategy in my own school to great effect.

- Use the no opt out strategy from TLAC – don’t allow any students (let alone disadvantaged to simply say ‘I don’t know.’ Give them wait time, let them look over their notes before attempting answer. Circle back to them to ensure they have understood.

- Use ‘no hands up’ when questioning. This blog from the Learning Scientists highlights the negative affect ‘raising hands’ can have on student performance… Asking students to raise their hand to signal their achievement (when they knew an answer) highlights differences in performance between students, making it more visible. This can lead to students in lower social classes, or with lower familiarity with a task, to perform even worse than they would have.

Frequent quizzing. As already stated this is a great routine for getting students into a class and settled whilst also benefitting their learning. As Joe Kirby suggests in his blog, we have over 100 years of scientific studies that frequent testing is the best way to disrupt the curve of forgetting. The best thing about low stakes quizzing is that teachers don’t need to grade, track or spend hours marking them. They can be self-marked by students as teachers explain the answers and knowledge gaps can be addressed immediately.

- TRY: For the next six weeks instead of your planned starters try quizzing students at the beginning of each lesson using the ‘last week, last month, last term’ approach. What do you notice about their learning? What if students were quizzed at the beginning of every lesson, every day, every term? Would that help balance out the knowledge deficit?

Modelling. When teaching it’s important to model what great performance looks like in your subject and even more important that you model the process (meta-cognition) of how to approach problems / tasks. The EEF see meta-cognition as one of the most impactful learning strategies that especially helps disadvantaged students.

Feedback. This is another strategy which the EEF deems to have high impact on student performance. The most important thing about feedback is that students do something with, ideally acting on the teachers feedback to improve their work and consolidate or extend their understanding. How can teachers be more meticulous with their feedback for disadvantaged students?

- TRY:

- Marking little and often rather than a whole set of books in one go. I’m not a fan of ‘marking PP books first’ as this suggests that other student books are less important or may receive feedback that is of less quality then the books marked first – which is wrong.

- Try whole class feedback that addresses common misconceptions.

- When conducting a feedback lesson have your annotated seating plan in your hand and visit the disadvantaged students frequently to ensure they have understood and are acting upon your feedback.

Read. Encourage students to read lots. Make it part of your lessons and teaching rather than an ‘add on’. As Katie Ashford describes, a good reading lesson should follow these principles…

- In any lesson, reading should primarily be for comprehension. Pupils need to understand what they are reading, and so the teacher should pause at appropriate moments and check for understanding.

- Reading is an opportunity to improve pupils’ fluency and ability to read with expression. Teachers should therefore model good reading and ask pupils to read aloud (year 7s love this, so get them into that habit then- it’s harder as you go up the school, in my experience).

- Reading is an excellent opportunity to improve pupils’ vocabulary. Teachers should pause to explain the meaning of key words, and may want to give further examples of new words used in context.

A list of strategies for reading in lessons can be found here.

TRY: As part of explaining a new concept give students a a passage of text to read that explains the concept (perhaps with a diagram if appropriate) to compliment your explanation. This could be read as a class or individually. If this habit is formed over a time it could help increase student vocabulary, fluency and understanding whilst enabling them to read outside of their normal experience (e.g. scientific articles, classical literature, e.t.c.).

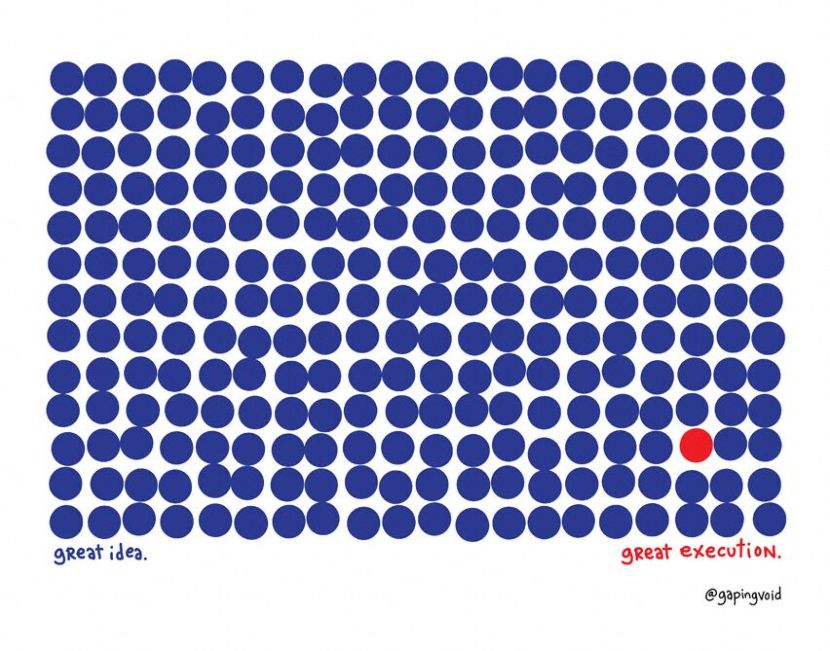

Image: @gapingvoid

The thing that does make a difference, not just for disadvantaged students but for all students is effective teaching and learning. The challenge for teachers is ensuring that disadvantaged students get overexposed to this every lesson as it is those students who stand to gain the most. Be bold. Be courageous. Have relentlessly high expectations of all students. Form effective habits and don’t leave anything to chance. We only get one chance to help all students access the opportunities they all deserve.

“To build a better world we need to replace the patchwork of lucky breaks and arbitrary advantages today that determine success–the fortunate birth dates and the happy accidents of history–with a society that provides opportunities for all.” [Malcolm Gladwell]

High expectations & brutal honesty – are we asking the right questions?

Asking whether something works or not in education is an endless, perilous quest that normally results in argument, resentment and division. It’ll be more useful to ask “under what conditions does it work.*” The more I read about Michaela Community School the more I’m convinced that high expectations and brutal honesty are whats needed in schools to help young people exceed their expectations. It seems (from the outside looking in – I’m yet to visit) that Michaela have created the conditions that enable their core values so that students can flourish.

Following an article published in the Sunday Times, Twitter was alive with debate about Michaela’s approach. I’ve yet to visit the school (hoping to visit in early 2017) so I’m trying to keep an open mind, but have read blogs from many of their staff. Regardless of whether you agree with their approach or not, one thing that has impressed me (from the numerous blog posts/articles/presence on Twitter) is that they appear to be asking the right questions. Their answers may not fit your view of education (there are a few things I’ve read that are currently at odds with my own views) but the questions they are asking will almost certainly be useful in moving your thinking forward. If anything it’s refreshing to follow the development of a school that is challenging the status quo – committing to long term strategic goals rather than settling for short term quick wins.

Here’s a few questions (I’m sure this is just the tip of the iceberg) that Michaela has prompted me to consider:

School ethos:

- What is the purpose of our school?

- Can this be summed up in one phrase?

- How is this communicated to staff, students & parents?

- When we say ‘high expectations’ what do we actually mean (down to the detail of day to day life in the academy)?

- What do we mean by ‘high expectations’ of:

- Teaching?

- Learning?

- Uniform?

- Behaviour?

- Manners?

- Communication?

- School environment?

- What do we mean by ‘high expectations’ of:

- How are new students inducted into the school?

- Is an assembly and some extended tutor time enough to train students in the detail of school rules and expectations?

- Would allocating sufficient time (2-3 days to a week) to effective routines/rules at the beginning of the school year save time later on and reduce consistency amongst students/staff?

- Is the school culture dialled in so that everyone is moving in the same direction?

- Is the culture amongst staff to a level where people feel they are able to give their honest opinion and be part of the development of the school?

Teaching, learning, curriculum & assessment:

- What is learning?

- What are the most effective learning habits for students to develop?

- What do we mean by effective teaching? How do we know?

- What is the best way to structure a curriculum to enable learning?

- How is learning interleaved over time (to increased long term memory retention)?

- How can assessment be used to challenge students and provide useful data that enables teachers to plan effective sequences of lessons?

- What do students need to know? How is this communicated to students?

- How do we convince students that success is achieved through a series of habits (and that anyone can achieve this)?

- What is effective homework?

- How often should it be set?

- Should there be a tight whole school approach or complete teacher autonomy?

- How will homework be monitored?

- What happens if homework is not completed to an acceptable standard?

- Is marking every single book an effective use of time?

- Are teachers happy, appropriately challenged and given enough support to teach well day in day out?

Literacy & numeracy:

- What is the most effective way to catch up students who are already behind with literacy & numeracy upon arrival?

- How is this embedded across all subjects becoming part and partial of every lesson?

- What is the most effective way to accelerate the progress of weaker readers?

- What role does reading play in school, every day?

- How do we support students to truly love reading and see it as a worthwhile use of their time?

Behaviour:

- What are our expectations of every student every day?

- What systems are in place to deal with disruptive behaviour?

- How do we ensure consistency across all staff?

Recruitment:

- How do we get the ‘right people on the bus’?

- Is the school vision / value so clear that potential candidates knowingly opt in?

Approaching Michaela through the lens of ‘right or wrong’ is a waste of time. Use their model to challenge your thinking, your values / beliefs and most importantly what purposeful education is so that we can all continue to do whats best for the students. For doing precisely that I’d like to thank Michaela and its staff for making me think.

*stolen from Dylan Wiliam but couldn’t find the exact quote.

Plan for learning.

If learning happens over a period of weeks, months and years.

Is lesson planing always carried out with student learning in mind?

Recently I have led a series of talks/sessions/workshops on the challenges of leading teaching & learning across a school. What has struck me as somewhat odd is the number of people that hear the phrase ‘teaching & learning’ but only really register the ‘teaching’ part. Teaching without any understanding of how people learn or what learning is, conjures up thoughts of the blind leading the blind. What does your school focus on? Is their balance between teaching and learning with links between the two?

After reading books like ‘Why students don’t like school’ and ‘the hidden lives of learners’ I can’t help but think about learning whenever I’m planning a lesson or reflecting upon my teaching. This has led me to reflect further on lesson planning and a few questions that teachers could consider, to focus the planning of a lesson to maximise learning:1. What is the desired learning outcome?

2. What do I want students to think about at different points during the lesson?

3. Will the activity make them think hard about the desired content or distract them from it?

4. How will I link new knowledge to students existing knowledge base?

5. How will I model the learning outcome?

What I think about when I plan a lesson.

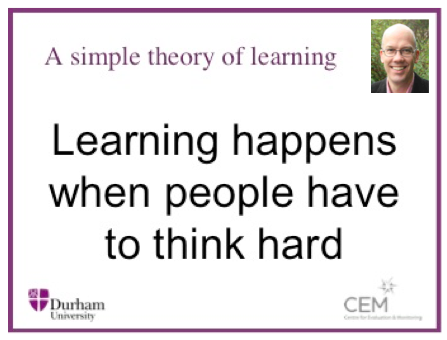

I always go back to a definition of learning by Professor Coe that has stuck with me. and stays at the forefront of my mind…

So I think about the one thing I want my students to learn and then design a sequence that will enable them to think hard about the knowledge and apply / practice the desired skills. If an activity does not contribute to the learning then it doesn’t form part of the lesson.

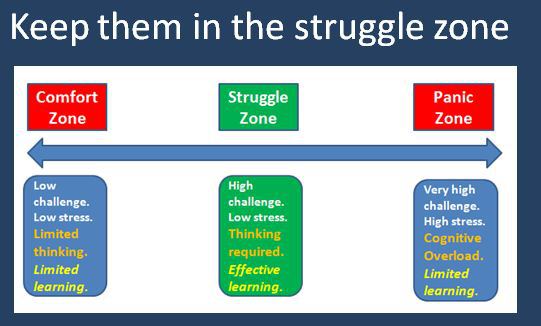

The spectrum below (created by Shaun Allison) expertly depicts what teachers should be aiming for – the struggle zone. Learning should be difficult enough that students grapple with the content but not so difficult that it flies straight over their heads or so easy that it doesn’t require any real thought at all.

What is the quickest path to the learning?On a recent trip to Malaysia (so recent I’m currently sat in my wife’s parents house in Malaysia writing this post) me and my wife decided to fly direct from London to Kuala Lumpur, with a 3 month old in tow it seemed like a sensible idea. Our objective was to get to Malaysia as quickly as possible with the least amount of hassle and distraction. Now we could have flown from London to Amsterdam, wait a few hours flown to Dubai, wait several hours before flying onto Kuala Lumpur which would have used up almost a whole day on travelling. This option might have saved us a little money but would have almost certainly used up lots of time and energy. This scenario made me think about lessons and the quickest possible route to learning.

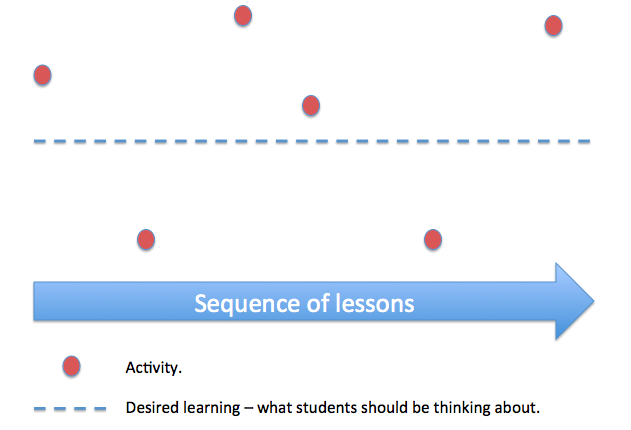

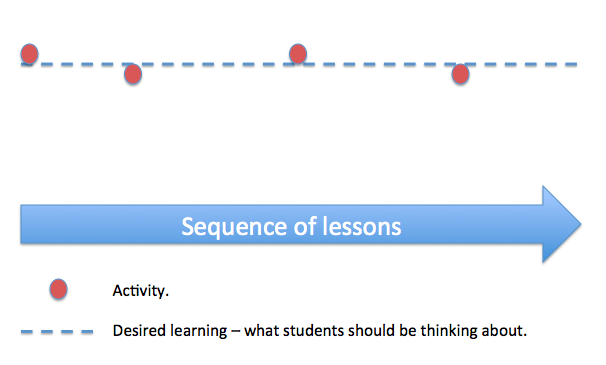

I’ve observed a number of lessons where the objective has been really clear on the learning that the teacher wants the students to engage with, but the students have been held back by a flurry of activities with questionable links to the desired learning. This leads me to think that as teachers, if there is a direct route to the learning we should take it. When planning a lesson, if the objective is for students to learn X why should they embark upon an array of activities that eventually lead them to X or miss the destination altogether? We sometimes get bogged down in planning lessons to fill time using multiple activities (that sometimes take us off course) to buffer the learning rather than getting straight to the learning.

Consider the two diagrams below – which one best represents your lessons?

When planning a lesson it’s important to keep in mind the learning and design activities that will enable students to think hard about the desired learning by spending time in the struggle zone and allow time for students to practice the application of desired knowledge / skills.

Habits of highly effective lesson planning.

Image via @pepsmccrea – http://bit.ly/1KigWIE

1. Start with the end in mind.

Excessive clarity – The clearer you are about where you want them to get, the better you’ll be able to help them get there.

2. Take the shortest path.

Don’t waste time designing overly complex learning experiences. What is the least I need to say to explain this concept to my students? What is the least amount of information I need to give them before they can get started?

3. Assess reliably and efficiently.

Hinge questioning Asking the whole class to: answer a multi-choice question using hand-signals; or show their thinking using mini-whiteboards.

Exit ticketing Giving students 3 questions to answer on a sheet of paper which they have to hand to you as they walk out the door.

4. Build learning that lasts.

Plan for thinking As Daniel Willingham so eloquently puts it, ‘learning is the residue of thought’. Plan what you want your students to think.

Anchor thinking David Ausubel tells us that ‘what students already know is the most important factor in what they can learn’. Design activities to help your students tap into what they know and make connections with what they’re going to learn about.

5. Anticipate the unexpected.

Increase your impact further by looking for points in your lesson where students are likely to struggle, make mistakes or develop misconceptions.

6. Move towards inter-lesson planning.

The relationship between lessons is just as important as what happens within them.

7. Plan better together.

Sharing your planning and practice not only brings fresh eyes to old problems and helps us articulate what we’re doing and why, but it also spreads our understanding of what works (and what doesn’t) amongst our profession.

Summary.

We often have lots of great ideas for lesson activities but must consider the execution of them and the effect they will have on the desired learning. When planning a lesson consider:

– working backwards from where you want students to end up.

– what you want students to think about at different points in the lesson and how your planned activities will foster that thinking.

– the quickest path to the learning – don’t waste time with lots of activities that just keep students busy – focus on tasks that enable students to grapple with knowledge / skills in the ‘struggle zone.’

The ‘Superman effect’ and ‘Purple cows’

I recently watched a video of Aral Balkan speaking about something he calls the ‘Superman effect’ which made me immediately think about lesson planning and designing remarkable experiences for the students I teach. If you haven’t seen it watch it now:

In the video @aral talks about something he calls the ‘Superman effect’ in design. How design is an art form that empowers, amuse and delights people. Great designers have the power to changes lives and give users exceptionally remarkable experiences that make them feel like a ‘superhero’ – the ‘Superman effect.’

Aral goes on to say…

Our lives are a string of experiences. Experiences with people and experiences with things. And we, as designers — as the people who craft experiences — we have a profound responsibility to make every experience as beautiful, as comfortable, as painless, as empowering, and as delightful as possible.

Now read the quote again but replace the word ‘designers’ with ‘teachers.’ Perhaps as teachers we have a duty to make students uncomfortable and allow them to struggle in order to learn, but the rest of the quote really rings true with me. As teachers we have to recognise that every interaction we have with young people is an opportunity to have a positive impact upon them. Teachers are artists and lessons are our art. Being passionate about our subjects mixed with a continued desire to improve and develop our pedagogy is key to providing the ‘Superman effect’ for our students. How can we make students feel like super hero’s in our lessons? We need to make them feel more excited about entering our classrooms rather than leaving them. Next time you’re planning a lesson consider the ‘user experience’ and make it remarkable.

In Aral’s extended version of his talk (see below) he also talks about how design gets compromised when companies have misguided CEO’s who seek to dictate the journey to success and quite often get it wrong. How true is this in schools? How many times have SLT implemented policies / procedures with little or no consultation from staff (thankfully this doesn’t happen in my school, but I’m sure we’ve all heard a horror story in our time…)? The way to unleash potential is to ensure that leadership is distributed across the school and that power is dissolved to all staff. Let the people who are closet to the action have a say in the critical decisions, empower them to lead.

Aral Balkan: Superheroes & Villains in Design from Thinking Digital on Vimeo.

Seth Godin talks about being remarkable in his book ‘Purple Cow.’ He talks about truly remarkable products / ideas and people or as he calls them ‘Purple cows.’ I believe teachers have a responsibility to be remarkable and provide remarkable experiences for their students. ‘Good enough’ or ‘that’ll do’ or even ‘Very good’ is a one ticket to mediocrity. It’s not remarkable. You are an artist with talent waiting to be unleashed. Be creative. Safe is risky. Don’t be boring. Be remarkable in everything you do.