Tagged: grit

GCSE Computing revision materials.

GCSE Computing revision materials.

This is a work in progress. This post will be updated regularly over the next few weeks to cover the OCR GCSE Computing syllabus. The resources can be easily adapted if needed. Feedback welcome!

Read more about the approach to revision I’m trialling here.

1. Computer Systems

Self-reflection[PDF] [.DOC] | Chunked revision booklet [PDF] [.PPT] | Multiple choice questions [PDF]

2. Hardware

Self-reflection[PDF] [.DOC] | Chunked revision booklet [PDF] [.PPT] | Multiple choice questions [PDF]

3. Software

Self-reflection[PDF] [.DOC] | Chunked revision booklet [PDF] [.PPT] | Multiple choice questions [PDF]

4. Data representation

Self-reflection[PDF] [.DOC] | Chunked revision booklet [PDF] [.PPT] | Multiple choice questions [PDF]

5. Databases

Self-reflection[PDF] [.DOC] | Chunked revision booklet [PDF] [.PPT] | Multiple choice questions [PDF]

6. Networks

Self-reflection[PDF] [.DOC] | Chunked revision booklet [PDF] [.PPT] | Multiple choice questions [PDF]

7. Programming:

Self-reflection[PDF] [.DOC] | Chunked revision booklet [PDF] [.PPT] | Multiple choice questions [PDF]

#neverstoplearning

Increasing bandwidth – Planning a revision session.

Talent isn’t born. It’s made.

In Daniel Coyle’s book ‘The Talent Code’ he travels the world to seek out groups of very successful people and in an attempt to discover why they are so successful. Through his observations of multiple different groups from musicians to football players he noticed one recurring trend – deep practice. In fact he has created an equation that summarises the elements needed to make progress and succeed at something. It looks like this…

Ignition or primal cues relates to the motivation a person has to be successful in the first place. As a teacher I believe it’s part of my job to talk to students about what motivates them to succeed. Some students are able to easily articulate this. whereas some will need some help finding the reason why they need to be successful. Either way I need to support the students I teach in understanding their ignition to succeed.

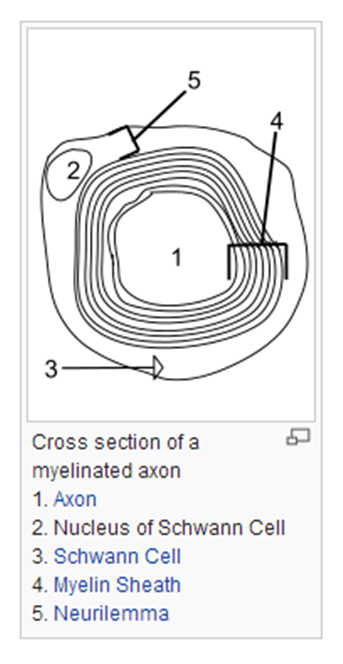

Continual deep practice is about increasing the amount of myelin in the brain*. Have a look at this great interactive guide to Myelin on Daniel Coyle’s website. Myelin is…

Myelin is a lipid and protein sheath-like material that forms an insulating cover that surrounds and protects nerve fibres.

Structure of a typical neuron from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myelin

The general idea is that the more myelin you have insulating your nerve fibres, the faster impulses (or information) can travel between nerve cells. Some scientists believe that myelin can be increased with regular deliberate practice. It’s similar to bandwidth in the speed of an internet connection. The more bandwidth you have the faster the transfer of data. The more practice you put in, the more the myelin wraps around the nerve fibre increasing the bandwidth (the diagram below shows this in a bit more detail). It’s worth noting that this works both ways and needs to be maintained with regular practice.

Cross section of a myelinated axon taken from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myelin

Daniel Coyle uses the example of Brazilian soccer players to explain deep practice in action. From an early age they play a game called Futsal and they continue to play it into their teenage years. Futsal is played on smaller court with a smaller ball which means that players will touch the ball more often than playing 11 a side on a full size pitch. This is deep practice. It’s quality controlled by a master coach (someone with expert knowledge of the game / subject) who intervenes with striking impact to ensure learning is meaningful. The video below examines more examples of where deep practice has produced successful outcomes.

How does this apply to revision?

If we want students to be successful in exams then they need to practice – sounds simple enough, but is not entirely true. If we want students to be successful they have to fine tune their practice so that it is deep, deliberate and regular in order to build up a thicker insulation of myelin. What follows are few strategies that I am currently trialling to achieve this.

1) Regular self assessment with input from the teacher.

It’s important to let students assess their own strengths and weaknesses when it comes to a topic to revise. Teachers are the master coaches described in ‘The Talent Code.’ We have to know our students well and track their learning and use this information to intervene with self assessments so that students know what they are actually good at and areas that they need to improve. The key to good revision (I believe) is to focus more time on the weaker areas (being deliberate) rather than spending lots of time revisiting knowledge/skills that a student is already competent in. Below is an example of a self-assessment I have used with students. The black ‘X’ represents the student response. The green Y’s represent my response based upon prior testing and my knowledge of the students competencies through questioning and classwork. If I have agreed with the students response I have not added an additional symbol.

The grid provides a clarity. Students get validation for what they think they already know or an opportunity to discuss area for improvements. It also helps students to focus in on the weaker areas and thus provides a starting point for revision.

2) Chunking information.

Once students have self assessed their strengths and weaknesses and they have been agreed, they can then begin revising required knowledge. In order to not overload the students working memory I have created a resource that chunks the information down in smaller sub-topics (see the list on the self reflection diagram above). Each sub topic has a series of questions that students answer in an open book environment. Example answers to these sections are released to students once they have attempted to answer them. They also have access to past paper exam questions and answers. Students are free to work through this revision pack using the self assessment as a rudder to guide them towards topics that will require more attention.

3) Regular rigorous multiple choice tests.

The ‘chunked’ revision materials are sync with a multiple choice test. I have created the tests using Joe Kirby’s brilliant posts on designing rigorous multiple choice tests (Post 1 | Post 2). I’ve attempted to increase rigor by adding more incorrect answers that are based on common student misconceptions.

The tests can be taken multiple times and using a platform like Edmodo means the tests are also tracked and scored without the teacher lifting a finger. Edmodo also allows students to go back through the test and see where they dropped marks.

A key element here is frequency and over a 6 week revision period it’s important to space the timing of these multiple choice tests to aid retention. As Joe points out in his most recent post on curriculum design,

Repeated retrieval improves long term retention: frequent quizzing prevents forgetting.

Read more about this here at Joe’s blog.

4) Regular ‘Walking – Talking’ mock exams.

One new strategy that has been trialled at my school this year has been ‘walking-talking’ mocks in all subjects. For those not familiar here’s how they work. The students revise for a mock as normal. When the mock exam takes place the teacher walks them through the first question and then gives students an appropriate amount of time (depending on the number of marks available usually) to complete the question and then get some instant feedback on how well they did. It’s hard to judge the real impact of doing this exercise but it certainly helps students feel more comfortable in exam conditions. I know I have been guilty in the past of running a mock exam in ‘exam conditions’, students tend to score poorly on it, get feedback but didn’t get an opportunity to re-draft answers (my fault) and the whole scenario was demotivating and not very productive. A walking-talking mock provide students to feel success in an exam environment. This new found motivation can then be used to drive revision sessions. As the year goes the strategy is to get students to sit 3-4 mock exams and by the end of the process provide them with less and less support as their confidence grows.

This post is by no means a ‘you should run revision sessions like this’ post. It’s a reflection on some of the ideas that have inspired my thoughts around how to do revision better. It is very much a work in progress and feedback is very much welcome!

I often tell my students to not be upset with the results they didn’t get from the work they didn’t do. I feel the same and care deeply about their results. When my students walk into the their exam I want to make sure I’ve done everything within my power to ensure they succeed.

Image via @gapingvoid – http://gapingvoid.com/

Further reading:

Myelin – by Daniel Coyle

How to grow a super athlete – by Dainel Coyle

The myelin in all of us – by David Shenk

Why use multiple choice tests – by Joe Kirby

How to design multiple-choice questions – by Joe Kirby

Research on multiple-choice questions – by Daisy Christodoulou

Walking, talking mocks: are mock exams the way forward? – by Martin Jones

Hardwiring learning and effort = success – by Domini Choudhury

*I am not a scientist. For more information on myelin please see this interactive guide or even better still, read Daniel Coyle’s book ‘The Talent Code.

#neverstoplearning

The Dip.

Ever felt like giving up on something? A project, a run, a blog post, organising an event, revising for an exam? If the answer to this question is ‘No’ I applaud you. You are either an extremely ‘GRIT-y’ person or perhaps you haven’t found a real challenge yet. If you answered ‘Yes’ then you have experienced the ‘Dip.’ In this, the first in a series of posts that explore motivation, GRIT, character strengths & growth mindset, I’m hoping to summarise what I have discovered from reading a series of books on these areas and what potential impact I believe it could have in the classroom. This first post looks at the bigger picture and addresses the general myth that successful people ‘never give up.’ In Seth Godin’s short book ‘The Dip’ he looks at why some businesses, organisations and people are successful and why some are not. Over the timeline of any successful project he argues that more often than not there is a ‘Dip’ where things get hard, more effort is required and the honeymoon period of the initial idea ends. The dip looks something like this:

The Dip is the point in a project whereby people leading make a decision. Is the outcome worth the extra effort and resources? Successful people are able to make the tough decision to either persevere because the outcome is worth the extra effort and resources or quit and invest their time, effort and resources into something that will be truly remarkable instead. Being able to successful make that decision at the point of the dip is tricky, risky and requires some experience, clear bigger picture thinking and the confidence to quit. Godin suggests the ‘Dip’ is the secret to success…

…the Dip is the secret to your success. The people who set out to make it through the Dip – the people who invest the time and the energy and the effort to power through the Dip – those are the ones who become the best in the world. They are breaking the system because, instead of moving on to the next thing, instead of doing slightly above average and settling for what they’ve got, they embrace the challenge. For whatever reason they refuse to abandon the quest and they push through the Dip all the way to the next year.

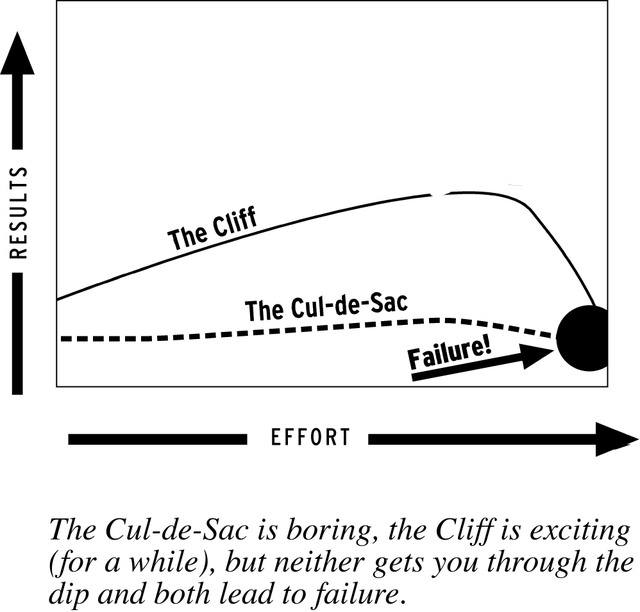

If something is worth doing then it will probably involve a Dip. But not always. How do we know it’s time to quit something? Have a look at the curves below:

Godin talks about knowing when to quit if the project curve looks like a ‘Cliff’ or ‘cul-de-sac.’ The cul-de-sac is described as…

…a situation where you work and you work and you work and nothing changes. It doesn’t get a lot better. it doesn’t get a lot worse. It just is.

Godin describes the ‘Cliff” as…

…a situation where you can’t quit until you fall off, and the whole thing falls apart.

The main problem is knowing when you are on either of these two paths. It would be quite easy to mistake the Dip for the ‘Cliff” for example. Having a clear goal, starting with the end in mind will help you determine what path you are on. Revisiting the purpose regularly, reflecting and being brutally honest with yourself will also help – sometimes it may be easier to continue a project (even if you suspect a ‘cul-de-sac’) then quit and devote your time and resources to something will make a bigger dent in the universe.

I experienced the Dip recently whilst organising a teach-meet. After the initial buzz of announcing that I was going to host a teach meet for 200 teachers I was hit by the never-ending list of things that needed to happen in order for the event to be a success. Coupled with a full teaching timetable and responsibilities within my department – there was a point (if I’m being honest) where the thought of quitting crossed my mind. My goal was to put on a truly remarkable event and if I didn’t have the time and resources to do that, perhaps I should focus my time and resources into something else. However the end of goal was too important and I instead decided to lean into the Dip and persevere (something I’ve learned from ultra running). Having attended other teach meets I knew how inspirational these events can be and how much they make teachers think, re-focus and offer opportunities for teachers to take ideas that can have a positive impact on students.

Links to teaching.

As a teacher I’ve certainly had many moments where I’ve felt like quitting something because the outcome didn’t seem worth the time and effort. There have been times when I’ve powered through the Dip and had some truly amazing lessons, CPD sessions, e.t.c. There have also been other times where in hindsight I would have been better off quitting earlier and re-focusing my time and effort. But still I learnt from those experiences so all is not lost. From reading Godin’s work I will definitely be thinking of the curves mentioned earlier in this post when planning new department and school wide projects. It has also made me think about planning lessons. In a lesson or scheme of work when will students experience the Dip? What will students be thinking during the Dip? What action should I take? I believe this is where GRIT, character strengths and the growth mindset model fit in. These habits can be used to help navigate through the Dip. In my next post I’ll be exploring these habits and how they can positively influence learning.

Quick wins #1 – Question tokens

First in a series of posts about quick wins in the classroom. The aim of these posts is to provide teachers with ideas that can be tried in their classroom with minimal preparation time.

Why? I wanted students to become more independent and rely less on me for help. Quite often I see students giving up too easily and going to the teacher for help rather than persevering with a problem. I’ve also noticed that students ask a lot of lazy questions (when they can ask an unlimited amount of questions) without any real thought behind them.

Possible solution? Question tokens. I gave each student three question tokens and set 2 rules for the entirety of the lesson:

1. You can only ask the teacher 3 questions throughout today’s lesson.

2. You can ask each other as many questions as you like.

Resources.

Question tokens (Download for free – please share with colleagues)

Outcome. I tried this with a year 11 GCSE Computing class who were working through some programming challenges. The question tokens encouraged students to seek advice from their peers and if this led to a dead end, they had to research a possible answer using the Internet or come up with a well thought out question to ask me. I witnessed the students demonstrating more GRIT then in previous lessons as they appeared to be quite precious of the question tokens – they would rather struggle through a problem and find a solution themselves then ask me for help. Quite remarkable!

#neverstoplearning