Lesson observations for ‘Genuine improvement’

If learning is invisible.

If learning occurs over long periods of time.

If teaching is led by an individuals’ beliefs and values.

If effective teaching is hard to agree on and to a large extent determined by outcomes (but not entirely).

Is it right to persist with inferring judgments on teachers and lessons?

It seems we’re trying desperately to measure something that is very difficult to quantify (if not impossible). “Weighing a pig doesn’t make it fatter” a colleague of mine said recently when discussing the grading of lessons. Does the grading of lessons actually detract from genuine, deliberate improvement? This made me consider an over arching question – what is the purpose of lesson observations? Are they to judge or are they to offer support and help develop teachers? Is it possible to do both? In my experience I’m not sure that it is.

The problems with grading lessons.

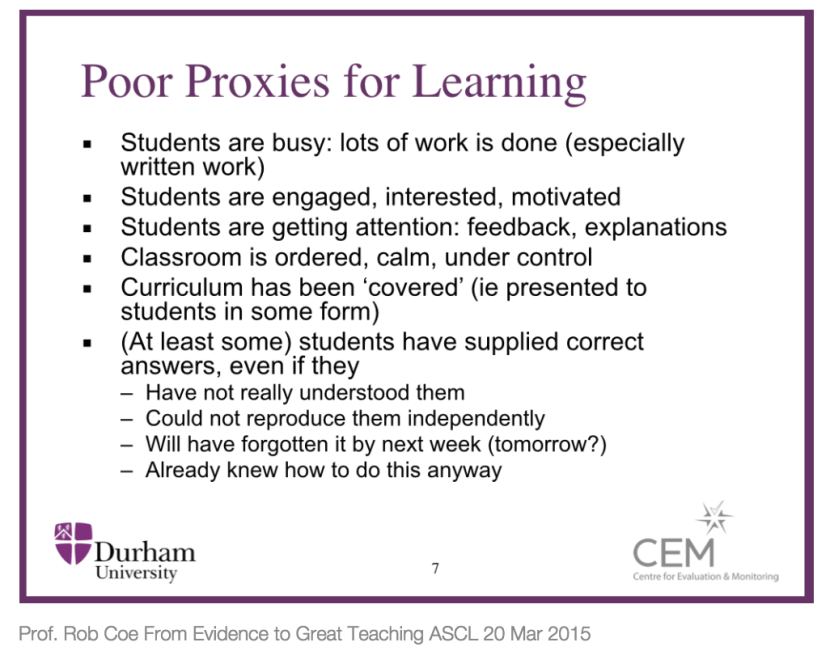

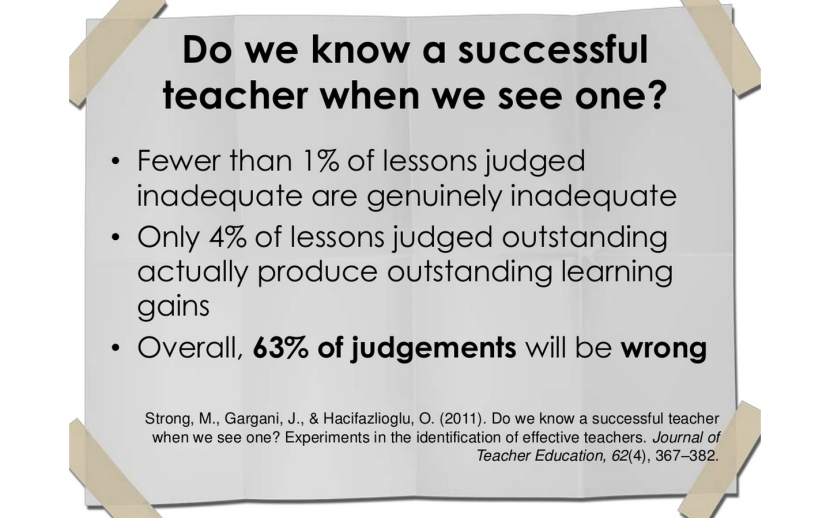

The main problem with trying to judge a lesson is that it’s hard to agree on exactly what great teaching is and in the moment of an observation it’s impossible to know what the learning gains for the students will be as a result of that lesson. If learning is invisible and it happens over long periods of time then perhaps all we can see in lessons is performance rather than learning and as Professor Coe points out, this generates lots of poor proxies for learning that we quite often use to grade lessons and assume learning is taking place.

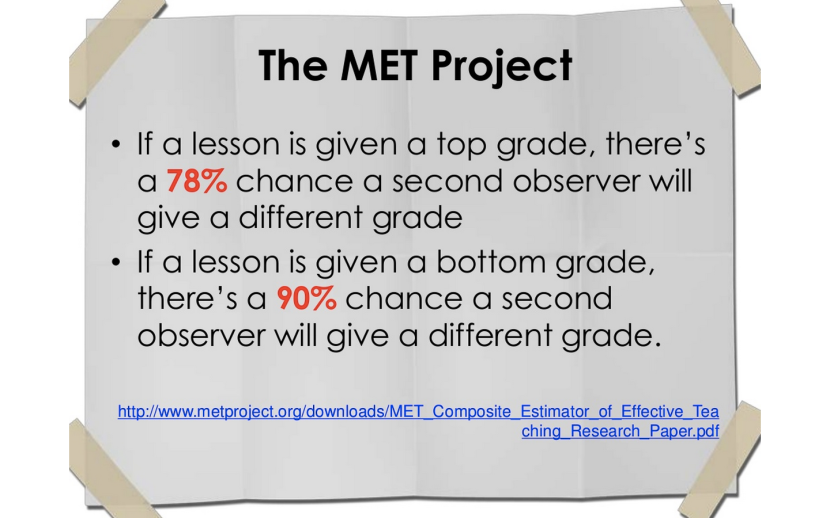

Despite a shared vision of improving the outcomes for young people, because the act of teaching is based upon peoples own beliefs and values (which will differ from person to person) it’s very difficult to agree on ‘good practice,’ and quite often our own confirmation bias takes over when attempting to observe it. As a result you could say it’s unlikely that multiple observers will arrive at the same grade, which brings into question the reliability of grading individual lessons. This was evident in the MET project…

Questions around the reliability of lesson observations are further explored here…

If we consider Professor Coe’s ‘Poor proxies for learning’ is it possible to truly know whether a lesson is likely to produce good outcomes from a 20 minute observation? It’s easier to check for evidence of a schools ‘list of non-negotiables’ in lessons – have books been marked, is homework being set, learning objectives, e.t.c. This is made possible by their prescriptive nature. But can observers accurately predict outcomes based on this and the conditions in the classroom? We know that a calm, quiet classroom does not necessarily indicate that learning is taking place, however it quite often gets used as a proxy for learning during observations. Which leads to this question…How many lessons that are judged to be ‘outstanding’ produce truly outstanding outcomes?

Leadership matters.

The day the soldiers stop bringing you their problems is the day you stopped leading them. They have either lost confidence that you can help them or concluded that you do not care. Either case is a failure of leadership.

Colin Powell

As a senior leader how well do you know your teachers? How often are you in and out of lessons?

As a senior leader when was the last time a member of staff came to you for help regarding a tough class? In a thriving school that genuinely prioritises the improvement of teaching, shouldn’t this be fairly common?

As a senior leader, how much of your time is spent in lessons speaking to students about their learning, getting a feel for typicality of teaching across the school? This should be a daily ritual, part of your core business.

As a senior leader how much time have you spent with the teachers who consistently get great results? What have you learnt from them? Has this been shared?

People.

Teachers are people, not robots that can be pre-programmed. They have beliefs and values related to teaching and education. A teacher on a full timetable is an extremely busy person carrying a reasonable amount of stress with them on a daily basis, mainly because they care so much about their students. Lesson observations should serve to support, challenge and develop teachers but quite often in a graded system the added stress of ‘being observed’ leads to a culture of fear. This is probably caused by:

- a lack of clarity for teachers around what observers are looking for in lessons

- a lack of clarity for observers around what they should be looking for in lessons

- subjectivity of observers and teachers

- what will happen next should a teachers lesson not be ‘up to scratch.’

If teaching is the most important factor in achieving great outcomes for young people, do we really spend enough time trying to genuinely improve it? Does a graded system help create a culture of improvement or distract from it? Does a graded system inspire teachers to improve or does it burden them with unnecessary stress? Does a graded system sharpen the focus of improvement or blur it beyond recognition?

Genuine improvement.

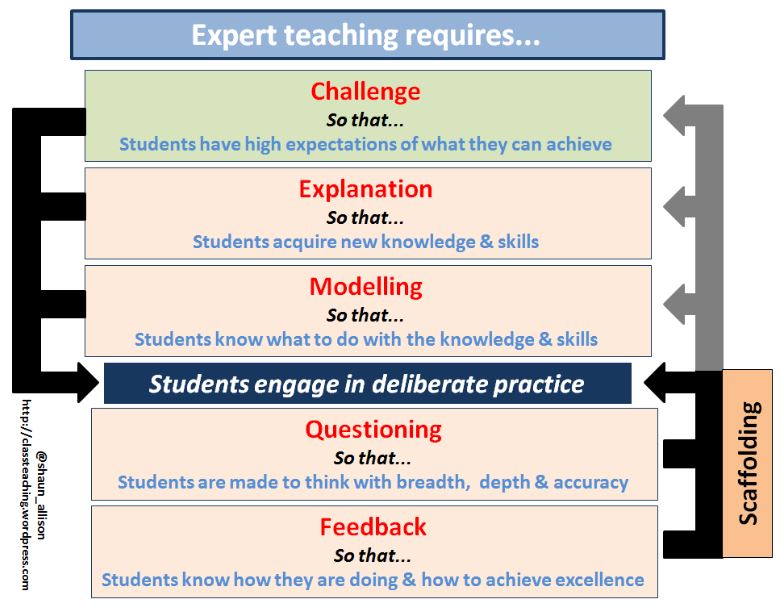

It’s very difficult (if not impossible) to agree on a list of prescriptive teaching strategies (and Ofsted don’t presbive any methods of teaching) but it’s easier to agree on elements of great teaching. When I think about elements of great teaching I tend to look no further than Shaun Allison’s fantastic model.

Whenever I revisit this model I find it difficult to tweak or change it. When I share it with colleagues it just seems to make sense to both them and me. How teachers go about implementing the above model into their lessons / series of lessons should be down to them. What this model looks like in a series of drama lessons it probably different to what it may look like in a series of maths lessons (however that does not mean that are things that cannot be learnt from observing both). Teachers should be trusted as the professionals that they are to do what’s best for the students.

The danger of moving away from a graded lesson observation system for some schools is that it could invite mediocrity, as most graded systems bring with them a very prescriptive set of teaching strategies. In some cases where schools are in need of improvement putting in a prescriptive structure can be the first step towards improvement – tighten up for good, loosen for outstanding. Tightening up will only take you so far. Grading lessons can show a direction of travel for improving teaching (as Dr Dan Nicholls explains here) but it also comes with excess baggage which can slow down the speed of travel. Perhaps a simple ‘secure’ or ‘developing’ may provided a stepping stone to merging the two schools of thought on grading lessons, e.g. “From the evidence collected in the lesson the questioning observed appears secure because… Further evidence from talking to the students suggests…” However this opens the flood gates of subjectivity, which can be curbed with prescription and eventually takes back to square one.

What is the alternative?

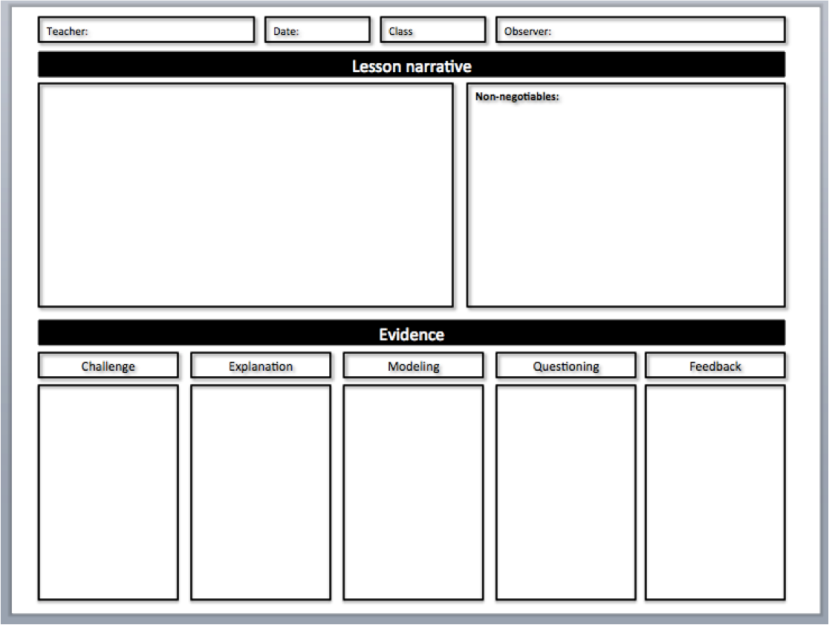

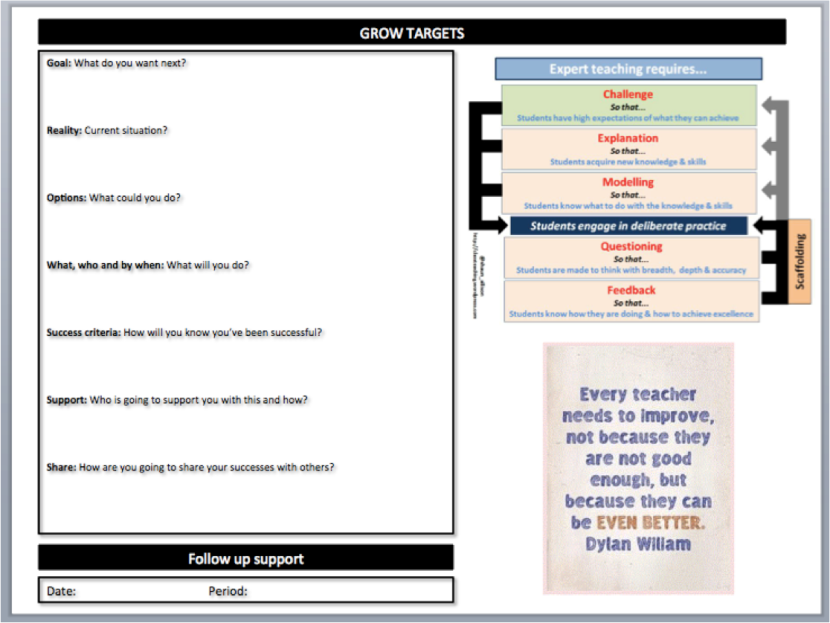

What if instead of trying to judge the teachers / lessons we adopted an approach where observers go into lessons to learn. This could take the form of observers going into lessons to collate evidence for teachers (perhaps under the headings of Shaun’s expert teaching model above) with a view of feeding this evidence back to them, similar to a lesson study approach. Build a picture of what appears to happening in the classroom (feeding the pig) rather than making a judgement (weighing the pig). Evidence could come from questioning students about their learning, looking at student work, observing how students / teacher interact with each other as well as assessment data provided by the teacher.

What if observers gave live feedback to teachers based on their observations during the lesson instead of waiting hours, days or even weeks to feedback. Here’s an example. A lesson is underway and the observer is watching as the teacher delivers an explanation of a key concept using a subject specific key term. After the explanation the observer spends a few minutes questioning the students to gauge their understanding of the task they have been given and the key term being used by the teacher. Out of the several students that have been questioned by the observer they are all able to explain the task (what they have to do) but none are unable to articulate what the key term means. Using live feedback (rather than waiting for the follow up feedback session) the observer is able to give feedback to the teacher straight away who is then able to help move the students forward with their understanding of the key term. In the follow up meeting the teacher explains that they had been using the key term for a few lessons and despite explaining the meaning in the first lesson they had failed to continually reiterate the meaning of the key term through the series of lessons. Together the observer and teacher are able to collaboratively come up with a simple strategy of asking students to repeat back definitions of key terms during lessons and the teacher was set the target to make this habit across all their lessons. This also served as a timely reminder for the observer to continue to develop across their lessons. At a department team meeting later that week the teacher is able to feedback their experience to colleagues.

Collated evidence + clear collaborative target = genuine improvement(?).

Not only did this experience serve as a timely reminder for the observers own teaching but the other teacher involved had a small step to implement and experience some immediate success. The observer followed this up with another supportive observation where they the teachers new habit developing in real time and it allowed the observer to collate further evidence of what was happening in the classroom, for the teacher. How might this process had gone if I had graded the lesson? I think the point here is that there is no need to grade the lesson at all – making the simple more complex for no additional gain. All the teacher needed to know was what was happening in the lesson – what did the observer notice that perhaps the teacher did not? What are the next steps to improve? In hindsight (my confirmation bias may be at warp factor 10 here), but I think a grade being given in the example explained above could have diluted the feedback and perhaps stifled the motivation for improvement.

Collating evidence in the classroom.

Chris Moyse has already started some great work on evidence based lesson observations – read about it here.

The idea revolves around going into lessons to learn and help teachers see things that they may not notice during a lesson – very similar to the lesson study approach. I’ve started to develop a document (in its first draft – feedback welcome) to collate this adopting the principles of great teaching from Shaun Allison’s model.

Draft observation form [PDF version]

Judging the quality of teaching.

How do we judge the quality of teaching if lessons are not graded? We really get to know our teachers. If quality teaching is the most important factor in determining great outcomes then SLT and middle leaders should spend more time in classrooms. What if members of SLT blocked out an hour a day to get into lessons and provide live feedback to teachers in the teams they line manage (if the one thing that would move a school forward is the quality of teaching, is an hour a day manageable? Probably). This could also be used to ensure non-negotiables are being met reducing the need for additional book scrutinies, learning walks, e.t.c. This could be on a continuous cycle that creates an open door culture and encourages teachers to ask for help rather than shy away from it. This would help the school have much clearer picture of the typicality of teaching. Judging the quality of teaching would be qualitative, as Shaun Allison explains…

If we really need to assign numbers to teachers, based on a 30 minute observation, to know about the quality of their teaching, then we are doing something really wrong. We still know our teachers inside out – we know who the really great ones are, and who are the ones who need that extra support with a particular aspect of their work. Without the need for numbers. We know this by looking at their student outcomes, as well as by looking at and discussing their lessons, the feedback that they give to students and the work that their students produce during lessons and at home. We know our staff.

In order to genuinely improve teaching we need to stay focused on the main thing – the quality of teaching. We need to focus on how it can be improved and not allow anything to dilute or blur supportive feedback. We need to remember that teachers are people and that our best chance of improving the outcomes of students is to support and challenge colleagues through a trusted relationship built upon collaboration and a relentless desire to learn.

Summary.

- Grading individual lessons is difficult, unreliable and time consuming which often results in little actual improvement.

- Grading individual lessons does not always speak to the person, diluting and blurring the focus of improvement.

- How can lesson observations be used to improve teaching (feeding the pig rather than weighing it)?

- Live feedback during observations – why wait for a feedback session if it could help students in the moment.

- Collation of a variety of evidence including student voice, assessment data, work in books, e.t.c. to give teachers further insight into their lessons.

- Continuity – SLT take joint ownership of improving the quality of teaching with middle leaders through daily time spent in classrooms. Time spent here could reduce the need for additional learning walks.

Next steps.

More questions have been asked than answered in this post but I hope it has provided some questions to consider when attempting to improve the quality of teaching through observing lessons. I intend to follow this post up with a more strategic plan of how the points in this post would manifest themselves in school (the logistics) and potentially replace a graded observation system.

Further reading.

Learning is invisible – David Didau

Classroom observation – it’s harder than you think – Prof Robert Coe

Evidence based and reflective observations – Chris Moyse

To grade or not to grade… is probably not the question? – Dr Dan Nicholls

How can we make classroom observations more effective? – David Didau

Stop Ofsted grading – Joe Kirby

Life without lesson observation grades – Shaun Allison

Creating the conditions for great teachers to thrive – Tom Sherrington

Lesson Observations Unchained. A new Dawn – Tom Sherrington

Still grading lessons? – David Didau

Beyond lesson observation grades? – Mary Myatt

I think that much of what you are saying is both interesting. However things that you may wish to consider:

1) Why are observations necessary at all? You take it as a given that observations have to happen and go on from there. In the history of teaching which has spanned over thousands of years – observations have not been the single factor that has led to good teaching. The whole observation regime is tainted (unfortunately in many cases, quite rightly) with bullying and lacks credibility among teachers. How many observation results have been decided in advance by members of SLT who were keen to demonstrate their ‘impact’ or to prevent people from applying for promotions that people higher up wanted to go to their favourites? These are just two examples of the abuses but there are so many.

What do they achieve? If things are going wrong then it is not observations that uncover this, they merely confirm and maybe help pinpoint the problem.

Are they necessary? How did Heads and SLT in schools prior to the regime of observations hold their staff accountable? It is easy to forget, but not a good idea to, that the vast majority of schools have always been run well with good teaching and learning practices. That is why there are people taught pre-1988 who have succeeded in education, in achievements, in their lives. What enabled good teachers to be good teachers regardless of observations? Put the metaphorical baby back in the bath.

The year I achieved my best results was when I was observed for twenty minutes over the course of the entire year – no learning walks, no additional scrutinies. The head was secure in who was a good teacher and preferred to give them targets to achieve and let them get on with it.

Should you do this with teachers who are struggling? – of course not. But tell me honestly that you don’t already know within the first month of the teaching year who is doing well and who isn’t – especially in primary schools – the evidence is in the books, classroom, attitude of the teacher and the pupils. I’ve yet to meet someone struggling whose managed to cover it up well. There will be some but I would argue that are managing it regardless of the regime. Building a regime to root out potential failures is not a positive foundation for improving teaching and learning. Do you want to lead teachers or a witch hunt?

2) If you insist on observations maybe its time that it was standard for SLT to put their money where their mouth is – hypocrisy, perfectionism and false idealism are the biggest barrier to getting others to take on board what you are saying. Too often feedback sessions are based on an overinflated sense of what the person observing personally feels they could achieve teaching that lesson with those children. Yet more often that not they have never taught them. What would happen if they did? How would feedback and solutions given to the teacher change?

The person I respected the most was an ex-head who was not happy with my teaching of guided reading in my NQT year. She came in and taught the class and I observed her doing it. We then discussed my feedback again and she was able to revise some of her ideas as well based on how she felt in the class. In fact should SLT not teach classes they are observing teachers in as standard prior to judging the teacher? It would engender more respect and faith in SLT and some humility from SLT too – both of which are sorely needed. The great Jenny Moseley taught one of the most challenging classes I have ever taught in my career when they had moved on to the next year group and came out exhausted and unable to continue her training session. She told the teachers that she didn’t know how they kept themselves coming in each day. It meant something to hear that – she still taught them and got through it because she is an experienced professional. But the difference between a realistic assessment and unrealistic one is the difference between teachers developing and improving even when they have tough classes (which I have always had in my career).

3) Ensuring that acquisition of new knowledge and skills is not narrowly defined to teaching new concepts – consolidation has a place in teaching and learning, often the shallow learning that takes place in primary schools is due to the fact that children are constantly being moved on before they have mastered a concept. Defining these concepts as a group of staff is important.

4) Live feedback – like the Iris filming and feedback – can only work if based on trust. School politics and the lack of real management skills holds teachers and their careers back enough without additional means of harassment – if you want to find fault, demean and nitpick then there is always a way because by virtue of being human beings we are not perfect. The person giving live feedback needs to be trusted. Team teaching might be preferable as it involves planning together and teaching together – this would enable you to give a greater degree of support.

5) Learning walks, extra observations in class, lesson studies, gathering evidence that teachers are actually doing their job – in all honesty you sound so ingrained with the current mentality that I am not sure that you are in a place to deliver the much-needed reform. This all smacks of insecure managers with responsibilities they can not handle.

Maybe it is time to say that people should not be given management roles in school without qualifications – and I don’t just mean education management courses – I mean actual management courses in industries that demonstrate good management has led to success. Even if it means looking at the private sector. My experiences of being managed in the private sector (even when I was working among self-confessed sharks that are education recruitment consultants) have been way more positive because my managers were only there because that is what they were good at, whereas in education the thing SLT were good at was being teaching. It’s not the same thing at all and neither does it indicate the ability to be a good manager.

Ultimately what I am saying is rather than shoring up an existing regime, which has led to the most appalling attrition rate of any profession I can think of, is not worth it. A radical rethink is required in terms of roles, accountability, whistleblowing and the conditions of employment are required. We know you can sack us – but when has it been shown that using and abusing this fact has led to improvements in any field?